If you, like me, loved Gillian Armstrong’s 1994 film, “Little Women,” which starred Winona Ryder as the treasured iconic tomboy, Jo March, you might have been doubtful about the need for yet another Little Women film adaptation. Louisa May Alcott’s cherished nineteenth-century story, Little Women, has been adapted for stage and screen several times, but, for many viewers, the beloved Armstrong version was the definitive visual interpretation of the story. Well, that was the case until Greta Gerwig’s newest film adaptation of “Little Women” hit the theaters this past December. Gerwig’s film stands out not only because it maps new ground for understanding the intricate layers of meaning wrapped in the classic tale, but also because it is a piece of art in its own right.

Unlike previous film adaptations, which often downplayed the other March sisters to focus first and foremost on Jo, Gerwig’s version gives each one of the four March sisters (Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy) the same kind of adoring attention that Alcott showed them in her novel. In fact, I found myself relating to each sister several times throughout the film. As a whole, the film shows the simultaneous comings-of-age of the March sisters as they navigate the societal restrictions placed upon them in mid-nineteenth-century America. At the beginning of Gerwig’s film, the publisher who buys Jo’s scandalous tales instructs her that American audiences want to read about women who end up married or dead. Gerwig’s Little Women follows this directive, but in a quite ingenious and sly way.[1]

In general, Gerwig’s version unearths how the small, and, at first glance, the apparently insignificant components of childhood, actually turn out to be major factors that affect a whole life’s trajectory. Gerwig also dissects the ways in which gender, birth order, class, and social expectations can constrain or heighten one’s sense of self. As film critic, Alissa Wilkinson put it, Gerwig’s film “is clearly the work of a writer and director who has learned to pay loving attention to the small and beautiful things in life, and wants us to do so, too.”[2]

Gerwig’s take on Little Women jars the story to life with a corkscrew timeline that weaves in-and-out between two periods in the lives of the March sisters: the blushing, golden glow of childhood and the gloomier, cooler tones of young adulthood. In the original text, Alcott chronicles the fates of the sisters in a traditional, straight, linear narrative style. Gerwig, in contrast, cuts the original text apart. She anchors the film in the complications of the sisters’ young adulthoods while depicting their happier childhood memories in an almost fairy-tale, lyrical fashion of flashbacks. The result, then, is that the girls’ memories become tied together, with the rosy past and the more frosty-toned present crashing together to incite a mixture of emotions that range from sheer happiness to love and grief all at the same time.[3] This zigzag framework also nudges us, the viewers, to pay closer attention to the ways in which we all tend to romanticize our childhood memories when we find ourselves facing the bittersweet passage of time.

What is more, the dyad structure of Gerwig’s film allows her to tackle another significant theme of the movie: the complicated undertones embedded in the institution of marriage. Little Women was published in two volumes, with the first one coming out in 1868. After the first volume’s enormous popularity, Alcott began work on the second volume. Now, Alcott had originally intended for Jo to turn out to be a ‘literary spinster,’ quite like herself.[4] But, that would not do for Alcott’s publishers. While Alcott refused to marry Jo off to the fan-favorite Laurie, she did invent, in her own words, ‘out of perversity,’ the sour and officious character of Friedrich Bhaer as a ‘funny match’ for Jo.[5]

The two volumes of Little Women, though, show a clear before-and-after story with the idyllic, coziness of childhood filling the first volume and the sterner, societal imperatives each sister faced, with regard to growing up, accompanying a substantial bulk of the second volume. Paramount among these societal pressures is for the March sisters to marry. Even though Little Women acknowledges that children need to grow up, the heart of the story remains with the joy and excitement that saturated the first volume. Readers tend to connect most with Jo because she, like them, resists the idea that the sisters must leave their childhood bonds behind.[6] As literary scholar, Lara Langer Cohen, describes it, “Jo is angry, above all, because she gets the bitter tragedy of Little Women as no one else in the novel does. It tells a story about the bonds that knit together a family of women—of love nurtured with exquisite care—only to break up that family and transfer its bonds to an array of frankly disappointing men.”[7] In this manner, Gerwig understands the twofold nature of the Little Women text; her film embraces the story’s dual structure and it dives straight into its narrative implications.

As Gerwig leans into the film’s binary themes, she highlights the economic underpinnings that forced many mid-nineteenth-century American women into marriage. “As girls,” Cohen explains, the March sisters’ love was intended to be “manufactured only for export, to enrich the emotional lives of men.”[8] The historical foundations for the institution of marriage is a topic that I have covered extensively in my own research and work. As Gerwig’s film portrays in exquisite detail, especially in an excellent speech by Amy March, the legal boundaries of nineteenth-century American marriages placed sharp constraints on women’s civic autonomy. Once a woman married, for example, the law held that she was to be covered by her husband. This body of status law, known as coverture, presumed that a woman maintained no civic identity separate from her husband’s status. This is the historical basis for why it is presumed that a woman should take her husband’s last name after marriage. In treating women as “covered” by their husbands, coverture imposed several restrictions on married women, which included their inability to hold property, draft wills, control their earnings, sue and be sued, to vote, hold public office, serve on juries, and enter into contracts.[9]

In one of my favorite scenes from the film, Amy March confidently walks towards Laurie after he had admonished her for not believing that marriage should be based on love. As she advances on Laurie, she boldly lists off the restrictions that will be placed upon her once she marries. As she tells it, once she is married, her property will become her husband’s property, their children will be her husband’s children under law, and the legal system will bound her into a subservient position to him. “So, don’t sit there and tell me that marriage isn’t an economic proposition,” she concludes.[10] The March sisters are all different in how they confront the issue of marriage that stares each one of them in the face. For example, Amy, as film critic, Constance Grady, effectively puts it, is a “born winner.” She sees the rules of the game, and she wants to win. She wants to marry someone with money and status so she can ensure that she will have the resources to take care of her family and make ‘everything cozy all around.’[11] Gerwig’s Little Women, then, tackles the historical issues embedded in the institution of marriage head on. By framing the film in sharp halves with the gloomier young adulthood more present, and the honey-colored warmness of the sisters’ childhood past shown in memories, we can not only see but also feel just what the looming presence of marriage was threatening to take away from the March sisters: their occupational dreams, their creative freedom, and their bonds with one another.

Another gem from Gerwig’s Little Women is that it incorporates aspects of Alcott’s real life into the movie in an unprecedented degree. Gerwig’s version, for instance, films many of its scenes in Concord, Massachusetts around the Orchard House where Alcott spent significant years of her life. Still, we should get something straight. Louisa May Alcott and Jo March were not one and the same. As Alcott scholar, Harriet Reisen surmised it, Alcott was “not the little woman you thought she was, and her life was no children’s book.”[12] Perhaps, this is another reason I admire Gerwig’s film so much; the way she tells the story, especially the ending, pushes the viewers to realize that Jo’s story and Alcott’s life were not synonymous.

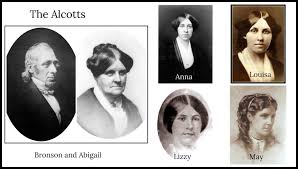

Of course, there are similarities between the feisty Jo March of the book and the real-life Louisa May Alcott who also had a forceful, determined nature. But, as Reisen makes clear, Alcott’s life was quite dark and atypical. Alcott’s success partly stemmed from her ability to create and market a wholesome image, but her actual life was riddled with strife, despair, and hardship.[13] While the March family were poor in a genteel way, for example, the real-life Alcotts were ‘poor as rats’ in the words of Louisa May Alcott.[14] Bronson Alcott, Louisa’s father, was a deep thinker who, in some ways, was ahead of his time. His philosophical mind was more preoccupied with pondering the contours of humanity, rather than with securing a steady source of income for his family’s financial stability. In his educational pursuits, Bronson was a passionate abolitionist and he made sure to include black students in his experiential Temple School in Boston in 1834. He also ensured that his daughters were educated, and he encouraged them to write about their personal experiences in their own journals. As well, the Alcott sisters benefitted from their father’s array of intellectual friendships. Ralph Waldo Emerson, for instance, financed the family’s move to Concord, Massachusetts in 1845, and Henry David Thoreau acted as Louisa’s tutor and de facto personal guide to the Concord forests.[15]

But, Bronson Alcott’s passion, stubbornness, and often times his arrogance, usually alienated his followers and wealthy benefactors, and his extremism frequently led to the closing of his educational ventures. His absolute refusal to accept a job that was not linked to his philosophical passions left his family with mounting debts and in dire circumstances. One of the family’s lowest points came in 1843 when the Alcotts endured a doomed experiment in communal living. Louisa, who was 11 at the time, and her family, nearly died from starvation after joining a small group of people attempting to put a few of Bronson’s more peculiar ideas into action. The members of Utopian Fruitlands, as the community was known, tried homesteading without livestock, refused to eat vegetables that grew underground (like carrots), and declined to have anyone conduct manual labor, with the noted exemption of Bronson’s wife, Abigail, who was tasked with the singular responsibility of cooking, cleaning, and caring for the community’s children.[16] As the winter of 1843 set in, Abigail and her daughters were left in a freezing attic room, with little-to-no food, with Bronson diving deeper into the Utopian Fruitlands community. (At this time, he had begun to question the need for a nuclear family as an organizing, social concept.) Realizing the dismal extent of their circumstances, Abigail arranged for her and her daughters to escape the community and live with a nearby family.[17]

After fleeing Fruitlands, poverty forced the Alcotts to move from rented rooms to rented rooms for an extended period of time. Bronson Alcott would eventually rejoin his wife and daughters, but a deep depression kept him from finding a steady income, as his illness caused him to stay in bed for weeks at a time. It was at this point that Abigail recognized that she and her daughters would have to rely on themselves for survival. Their need for food and shelter made it necessary for Abigail and her daughters to take up an array of work, often times laboring as domestic helpers, seamstresses, governesses, and teachers.[18]

The family found temporary relief when money from an inheritance that Abigail had received, and financial assistance from Emerson, allowed the family to purchase a homestead in Concord, Massachusetts in 1845. The homestead was named “Hillside.” The sisterly stories in Little Women are loosely based around events that unfolded at Hillside. In 1852, though, dismal financial circumstances once again pushed the Alcotts into a precarious situation, which caused them to sell Hillside to Nathaniel Hawthorne, who later renamed it “Wayside.” In the spring of 1858, when Louisa was in her late twenties, the family finally settled into Orchard House, where Louisa would eventually write the first volume of Little Women. With the success of Little Women, Louisa was able to fully step into the role of breadwinner for her family and ultimately provide them with stability and financial security.[19]

While Gerwig’s Little Women film slips small links to the realities of Louisa May Alcott as a person throughout the film—like the author’s love of running and her fascination with capturing lurid, sensational stories in her early writings—it is in Gerwig’s innovative retelling of the book’s ending that we see a glimpse of the actual course of Louisa May Alcott’s life. At the point where the film is forming the romantic climax in which Jo becomes engaged to Professor Bhaer, the film suddenly cuts to Jo haggling with her publisher, Mr. Dashwood. It turns out that Mr. Dashwood enjoyed reading the manuscript Jo had written about her family and he intends to publish it. There is a caveat, though. He tells Jo that she must guarantee that her leading lady ends up married by the story’s end. In response, Jo shows that she is a savvy negotiator. She declares, “If I’m going to sell my heroine into marriage for money, I might as well get some money for it.” She then shrugs, “I suppose marriage has always primarily been an economic proposition.” She goes on to inform Mr. Dashwood that she will marry off her main character, only if she maintains the copyright to her book and receives a larger percentage of the royalties.[20]

As Jo and Mr. Dashwood finalize the terms of the book’s publication, the film cuts back to Jo’s romance with Bhaer, which Gerwig sets in an amplified, warm-tone color palette, which is often used in typical romantic comedies. In the culminating scene, Jo and her sisters frantically rush to the train station to stop Bhaer from leaving town. Upon convincing Bhaer to stay, the couple share a dramatic, uplifting kiss in the rain. Next, we see the members of the March family enjoying a heavenly picnic at Aunt March’s former house, which Jo had previously inherited and remade into a school. We see Jo’s older sister, Meg, teaching acting lessons and her younger sister, Amy, teaching art. We also see Mr. Bhaer teaching the school children. The final scene of the movie cuts back to the cooler hues of Jo in the publishing office of Mr. Dashwood, as she watches her book, titled Little Women, be published.[21]

So, what do we make of this ending? What, exactly, is going on? The simplest answer is that the parts that we see from Jo’s mad dash to the train station and beyond—her reunion with Bhaer, her school, and her sisters’ teaching pursuits—are invented components of Jo’s story, which only take place in Jo’s novel after being created by Jo to fulfill her publishing agreement with Mr. Dashwood. But, Gerwig’s film resists simple, straightforward explanations. And, that is what makes it awesome. On Gerwig’s approach to the story, she explains that she was always looking for a “cubist, intuitive, emotional, intellectual kaleidoscope of authorship and ownership of text and chapter. Everything had to be multiple things, it could not ever just be singular. I had to have multiplicity in every moment, every line.”[22] Gerwig’s intention, then, was to convey two endings: the classically charmed ending from the original text and a new perspective on the form that happy endings can take, especially for women. “The hat trick I wanted to pull off,” Gerwig describes, “was, what if you felt when she gets her book the way you generally feel about a girl getting kissed? So, it’s not girl gets boy, it’s girl gets book.”[23]

On one level the final scenes in Gerwig’s Little Women calls to mind Louisa May Alcott’s actual life by suggesting that Jo might have not married after all, and that, perhaps, she lived her life as a literary spinster, just like Alcott. On a deeper level, though, Gerwig’s Jo/Alcott hybrid ending brings up the associations embedded in Alcott’s actual publishing dilemma, which was the pressure from her publishers to marry Jo off at the end of the second volume to sell her book. The idea that marriage is a sort of business transaction is a prominent theme in the film and it is highlighted again when Gerwig explicitly links Jo’s final decision to marry off her own heroine to Amy’s earlier decision to sell herself through marriage, as Gerwig had both Jo and Amy use the same language in their respective scenes to describe marriage as an “economic proposition.”

Through all of these elements, Gerwig underscores an important aspect of marriage: its potential economic logic for women. For Gerwig, marriage does not have to be romantic to make sense. As Gerwig explains it, marriage makes perfect sense as an “action of a woman who is living with profoundly curtailed choices, using her particular talents to make the decision that allows her to survive.”[24] I am sure plenty of viewers, like myself, were thrilled at the suggestion that Jo was able to maintain her independent spirit, publish her book, and remain single. But, the flipside of the ending, which followed the story’s more classic conclusion, allows room for us, the viewers, to understand why the decision to marry, even with all the limitations and harsh conditions marriage placed upon women in the nineteenth century, still might have represented the best path of survival for many women. That so many women did choose marriage, although it entailed the legal erasure of their civic autonomy, illuminates America’s long history of placing restrictions on women’s lives and controlling their opportunities. Gerwig’s film, moreover, points us in the direction of beginning to understand what the bleak implications of the decision to marry meant to so many women in nineteenth century America, and why those women felt they needed to endure those conditions in order to survive.

Now, as is the case with most films, Gerwig’s Little Women is not perfect. Even though the film is blooming with imagination, and while it pulls its viewers in through several magical apparatuses, a few reviewers have raised thoughtful critiques regarding the film’s small, but nonetheless, important shortcomings. A fellow historian, for example, claimed to me that Gerwig’s adaptation overly worships the single, independent woman writer and, therefore, her film betrays the varieties of femininity that Alcott depicted with affectionate detail in her novel. I think it is pretty clear that I disagree with that historian’s opinion of the film, as, my above analysis attests to, I see Gerwig dedicating several layers of her adaptation to portraying, and respecting, the different possible means through which women have found ways to lead their lives and express themselves, even amidst the historically punitive limitations society has placed upon them.

But, that historian’s critique does correspond to a point that literary scholar, Sarah Blackwood, raised in an article on the film in which she argues that Gerwig’s version is too committed to the theme of Jo being a “transformative feminist hero” who, as in the case of so many redemptive, individualist stories, somehow escapes, and, triumphs over the patriarchal system of oppression.[25] While I feel that is not a completely fair critique, since the film does leave avenues open for interpretation in which Jo does not completely overcome the system, I do think Gerwig’s adaptation strongly underscores the possibility of Jo retaining her independence, because Gerwig was trying to pay homage to the unique wonder that was Louisa May Alcott. Alcott, after all, did, in fact, remain single and was able to carve out a living for herself to support her family.

Another criticism of the film is that it is too devoted to white American womanhood. The film’s valorization of whiteness, critics argue, causes it to miss opportunities for incorporating a more fulfilling reflection of black American women’s stories. Writer Kaitlyn Greenidge, for instance, wrote in the New York Times that it could have been possible for Gerwig to include non-white characters like the real-life Ellen Garrison Jackson in the Little Women universe. As Greenidge explains, Jackson, who was nine years older than Louisa May Alcott, was a black activist who had grown up in Concord, Massachusetts around the same time as the Alcott sisters. Like the Alcotts, Jackson’s family was also dedicated to enacting radical social change. In 1866, moreover, Jackson, along with several other activists, filed a series of petitions challenging segregation in public transportation to test the nation’s first Civil Rights Act, which preceded Rosa Parks and the Montgomery bus boycotts by almost a century.[26]

In Gerwig’s efforts to update and expand the significance of Little Women, she could have easily incorporated Jackson into the story without risking historical accuracy. Ultimately, as Greenidge describes it, “many of the things that readers respond to in the story of the March family—the questions of how to live a life of moral fortitude in an immoral world; the fierceness of righting injustices that young girls feel when they encounter the world—are a part of the history of Ellen Garrison Jackson.”[27] So, why did the film skip over accounts that reflect the lives of black Americans like Jackson’s? Where, ultimately, are the stories of black Americans? Or, as Greenidge, a black American, adeptly puts it, “Where are we?” Those questions are important for helping us to unearth the thornier and more complicated stories, which can shed better light on America’s multidimensional past. A past that is not just a retelling of a history that many of us think we already know; a history that is not soaked in the myth of triumphant whiteness. Those questions, though, as Greenidge cautions, should “be an invitation to creation, not an end to conversation.”[28]

A significant limitation of Gerwig’s Little Women, then, is that it is primarily concerned with capturing the worldview of a very small, specific group of people. But, this limitation fails to eclipse the film’s brilliance. The film’s whiteness is bearable, Greenidge concludes, because it resists the conventional tendency of other stories preoccupied with whiteness to “declare that its worldview is the only one that matters and is fatally incurious about others.” Gerwig’s Little Women, Greenidge maintains, “is alive with curiosity and is intent on reminding us of the context in which the March sisters lived.”[29] Ultimately, Gerwig’s Little Women might only offer us a tapered perspective on the realities of mid-nineteenth-century America, but it is careful to nudge its audience into understanding that it is only giving a piece to a larger puzzle. In the end, Gerwig’s adaptation is remarkable because it encourages us to have larger, more meaningful conversations about our past and our present, and it invites viewers to realize the entertaining power of stories that finally allow women to dominate the narrative focus.

~Rebecca DeWolf, PhD

[1]. A.O. Scott, “Little Women’ Review: This Movie is Big,” New York Times, 23 December 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/12/23/movies/little-women-review.html (accessed 4 February 2020).

[2]. Alissa Wilkinson, “Greta Gerwig’s Little Women adaptation is genuinely extraordinary,” Vox, 20 December 2019, https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/12/20/21021183/little-women-review-gerwig-ronan-chalamet-pugh (accessed 4 February 2020).

[3]. Wilkinson, “Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” Vox, 20 December 2019; Scott, “Little Women’ Review,” New York Times, 23 December 2019.

[4]. Constance Grady, “The power of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women is that it doesn’t pretend its marriages are romantic,” Vox, 27 December 2019, https://www.vox.com/culture/2019/12/27/21037870/little-women-greta-gerwig-ending-jo-laurie-amy-bhaer (accessed 4 February 2020).

[5]. In the original text, Professor Bhaer is a middle-aged, unattractive German professor who disapproves of Jo’s sensational stories. The original character, moreover, is a far cry from the handsome intellectuals that we often see when he is portrayed in “Little Women” film adaptations. See Grady, “The power of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” Vox, 27 December 2019.

[6]. Ibid.

[7]. Lara Langer Cohen, “Sister Lovers,” Avidly: A Channel of the Los Angeles Review of Books, 19 July 2016, http://avidly.lareviewofbooks.org/2016/07/18/sister-lovers/ (accessed 4 February 2020). See also Grady, “The power of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” Vox, 27 December 2019.

[8]. Cohen, “Sister Lovers,” Avidly, 19 July 2016.

[9]. Rebecca DeWolf, Gendered Citizenship: The Original Conflict Over the Equal Rights Amendment, 1920-1963 (in progress).

[10]. Grady, “The power of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” Vox, 27 December 2019.

[11]. Ibid.

[12]. “Alcott: ‘Not the Little woman You Thought She Was,” NPR: Morning Edition, 28 December 2009, https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=121831612 (accessed 5 February 2020).

[13]. Ibid.

[14]. Grace Lovelace, “The New ‘Little Women’ Brings Louisa May Alcott’s Real Life to the Big Screen,” Smithsonian Magazine, 18 December 2019, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/new-little-women-brings-louisa-may-alcotts-real-life-to-big-screen-180973806/(accessed 5 February 2020).

[15]. “Alcott: ‘Not the Little woman You Thought She Was,” NPR: Morning Edition, 28 December 2009; Lovelace, “The New ‘Little Women’ Brings Louisa May Alcott’s Real Life to the Big Screen,” Smithsonian Magazine, 18 December 2019.

[16]. Lovelace, “The New ‘Little Women’ Brings Louisa May Alcott’s Real Life to the Big Screen,” Smithsonian Magazine, 18 December 2019.

[17]. Ibid.

[18]. Ibid.

[19]. “Today in History: Louisa May Alcott: Daughter of the Transcendentalists,” Library: Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/today-in-history/november-29/ (accessed 5 February 2020); “The Wayside: Home of Authors,” National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/mima/learn/historyculture/thewayside.htm (accessed 5 February 2020); and Lovelace, “The New ‘Little Women’ Brings Louisa May Alcott’s Real Life to the Big Screen,” Smithsonian Magazine, 18 December 2019.

[20]. Caroline Siede, “Let’s talk about the ending of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” AV Club, 26 December 2019, https://film.avclub.com/let-s-talk-about-the-ending-of-greta-gerwig-s-little-wo-1840449374 (accessed 5 February 2020); Grady, “The power of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” Vox, 27 December 2019.

[21]. Siede, “Let’s talk about the ending of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” AV Club, 26 December 2019.

[22]. “Sorting Through SAG, Critics’ Awards, and All the Rest,” Vanity Fair: Little Gold men (podcast), 12 December 2019, accessed 5 February 2020, https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/little-gold-men/e/65951984?autoplay=true; Siede, “Let’s talk about the ending of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” AV Club, 26 December 2019.

[23]. “Sorting Through SAG, Critics’ Awards, and All the Rest,” Vanity Fair: Little Gold men (podcast), 12 December 2019, accessed 5 February 2020, https://www.stitcher.com/podcast/little-gold-men/e/65951984?autoplay=true; Siede, “Let’s talk about the ending of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” AV Club, 26 December 2019.

[24]. Siede, “Let’s talk about the ending of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” AV Club, 26 December 2019; Grady, “The power of Greta Gerwig’s Little Women,” Vox, 27 December 2019.

[25]. Sarah Blackwood, “Little Women’ and the Marmee Problem,” The New Yorker, 24 December 2019, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/cultural-comment/little-women-and-the-marmee-problem (accessed 7 February 2020).

[26]. Blackwood, “Little Women’ and the Marmee Problem,” The New Yorker, 24 December 2019.

[27]. Kaitlyn Greenidge, “The Bearable Whiteness of ‘Little Women,” New York Times, 13 January 2020,https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/13/opinion/sunday/little-women-movie-race.html (accessed 7 February 2020).

[28]. Ibid.

[29]. Ibid.