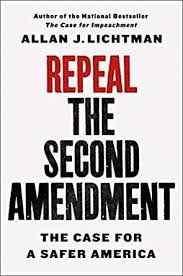

“A well regulated militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.” How did a once inconsequential, dismissed, and somewhat forgotten, sliver of the United States Constitution become such a hotbed of political strife and the source of overwhelming, mass violence? In Repeal the Second Amendment: The Case for a Safer America, Allan Lichtman, a distinguished professor of history at American University, draws upon a wealth of source material and meticulous historical research to explain how the National Rifle Association (NRA) has hijacked the history of the Second Amendment. In an effort to convince gun control advocates that they must pursue the repeal of the Second Amendment, Lichtman probes the history of firearms and gun regulations from colonial times to the present to detail the ways in which the NRA has manufactured a distorted history of gun ownership in America. Lichtman argues that the “iron triangle” of the gun lobby, the gun industry, and an array of pro-gun (mostly Republican) politicians have used a twisted and misleading history of the Second Amendment to advance their own interests, and enrich their pockets, while entrapping Americans into an endless cycle of gun violence.[1] To solve American’s gun violence problem, Lichtman concludes, the Second Amendment must be repealed.