The other day, while I was preparing my two-year-old son old for his afternoon nap, my three-year-old daughter looked up at me and asked what I had been working on earlier in the day. That day had been one of my workdays, a day in which I have a sitter come to watch my kids for three hours while I work in my home office.

Looking at my daughter, I gave her a sly smile and asked: “Holland, did you know mama is a doctor?”

She shook her head and scoffed: “You teasing me! You’re not a doctor!”

“But I am,” I replied. “I am a special kind of doctor and I am writing a special kind of book.”

“A book for me?” She asked.

“Yes,” I smiled as I thought of it. “A special book. A special book for you.”

I’ve been working on my book for a while now. In all honesty, it feels like a lifetime. Most of my family and friends would agree with that assessment. I’ve been working on this sucker for an insane amount of time. And, for good reason.

My book manuscript is based on my PhD dissertation,which I defended in the spring of 2014. My dissertation is over 400 pages long and based on a wealth of primary source materials (over 40 different manuscript collection and countless government records). It took years to complete that level of research and to organize the findings so that it made sense to my dissertation committee and academic peers.

Since it was a dissertation, the analysis and argument had to be based on original research. I had to uncover new information and my analysis had to provide a significant contribution to a particular academic field. After all, a PhD is only awarded when doctoral candidates have established that they know a lot of shit and (more importantly) that their research is creating new knowledge.

Now, a book manuscript is different from a dissertation in several key ways. First, with a dissertation you are trying to prove your authority on subject. So, typically as a result, you overload that sucker with citations, quotes, details, and other points of evidence. It’s also essential to demonstrate that what you are doing is different from what came before. So, you usually include a lengthy review of the previous scholarly literature on the topic. Needless to say, there is a lot to prove in a dissertation, which can lead to a lot of over explaining. The language tends to be technical and it is easy to slip into overly relying on the field’s jargon. Dissertations are also exceedingly structured, because you want your dissertation committee to easily discern your particular argument in any given section. As a result, dissertations include plenty of scaffolding (headlines and divisions), which produces a choppy narrative flow. With a dissertation-based book, though, your authority on a subject has already been established. If you were awarded a PhD, your reader assumes that you know (at least a bit) of what you are talking about. So, you don’t need to weigh down your work with excessive proof of its validity and originality.

For a dissertation-based book, you want the material to be more accessible and appealing to a larger audience. But, WAIT, this does not mean that you want to transform your study into a commercial product. For the most part, books that are based on dissertations are still geared towards an academic, scholarly audience. Most of them are published through academic (university presses), not trade presses. For up-and-coming scholars, it is more desirable to publish your book manuscript through an academic press, because the aim of those publishers is to produce valuable knowledge, not necessarily make profits.

The immediate goal for the author is not to make the book’s information entertaining and easily digestible. (In other words, it’s not to write a popular history book that people will read for fun on their beach vacations.) But, you do want to widen the scope of the project’s impact. Okay, what does that mean? If you are writing about a particular topic, let’s say the deathbed conversion of Charles II, your dissertation-based book will not only reveal new information about that specific topic but it will also focus-in on how that new information enlarges our understanding of broader historical trends, such as the intensification of print culture in Restoration England. So, the audience for this book would not only be fellow experts on Charles II, but also scholars and students of early modern European history.

Most importantly, though, when revising your dissertation for publication as a book it is essential that you tighten your work’s prose and sharpen its argument, so that you improve its narrative flow. You want to establish an original argument through the telling of a clean, seamless, intriguing story. So, you discard irrelevant details and excessive citations. You cut out the repetition, wordiness, and jargon. And, you present a clear analysis with significant, scholarly contributions.

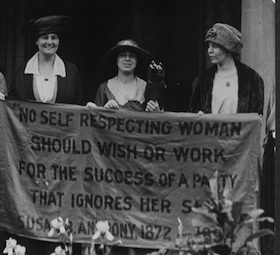

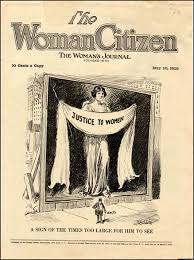

Okay, I know what you are thinking: “What the heck is your actual book about?” Good question. I have no idea. Just kidding! My book uncovers the competing civic ideologies embedded in the original conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). Previously, scholars have focused on investigating the reasons for why the amendment failed to gain enough state approvals for ratification in the 1970s and early 1980s.[1]While this previous body of work offers insightful information about the later ratification struggle, my study examines the earlier dynamic history of the ERA conflict from the 1920s through the early 1960s.[2]By taking a closer look at the too-often dismissed congressional source materials on the ERA, my book shows that the amendment did not sit idly in Congress until 1970. On the contrary, Congress held several hearings and issued a series of reports on the amendment. Moreover, my research shows that the economic turmoil of the Great Depression and the political upheaval of World War II did help amendment supporters create a considerable wave of support for the ERA that transcended traditional societal divisions.[3]

Now, there are scholars that have explored the ERA conflict before the later ratification struggle. These scholars primarily discuss the ERA struggle in the 1920s and early 1930s as a dispute among women, about women, and only concerning women. Moreover, they frame the conflict as a fight between two feminist groups over the trajectory of the women’s movement in the wake of the Nineteenth Amendment. According to their analyses, one group worked to expand women’s involvement in social reform programs while the other group single-mindedly focused on the effort to secure complete sexual equality through passage of the ERA.[4]In short, these scholars employ a female-centric narrative that emphasizes how the early ERA struggle affected the women’s movement.

While these explorations are important, my book maintains that the original ERA conflict is best understood not mainly as a struggle between feminist ideologies, but rather as a conflict between competing civic ideologies. Let me be clear, a crucial aspect of the original conflict did involve disputes among female activists over the priorities of the women’s movement after federal women suffrage. But, the focus on these disputes has concealed the larger story and significance of the ERA struggle. As I first uncovered with my PhD dissertation, the original ERA conflict not only involved female activists who had been associated with the suffrage movement, it also included an array of men and women politicians, intellectuals, labor activists, social reformers, and government officials. The participants not only argued over women’s constitutional status, they also contested the concept of citizenship.[5]

In my dissertation, I concluded that the original ERA conflict served as the terrain that allowed Americans to re-conceptualize the concept of citizenship so that it corresponded to women’s newfound status as electors. My book expands upon this analysis to further illuminate how the original conflict forged not only new conceptions of citizenship, but also a lasting belief in the equity of sex-specific rights, which continues to shape American society to the present day.

But, as I alluded to in the beginning, I am still working on my book. It is not finished. I do have polished drafts of three chapters, which I feel good about. But, I have three more chapters to heavily revise. I also need to write the introduction and rewrite the epilogue. So, there is a lot of work to be done, which is daunting at times.

I have completed a book proposal that I recently sent to an editor at an academic press. The proposal is currently under peer review. Peer review is an incredibly stressful process. It is a vetting process that academic presses use; it ensures that they only publish highly refined materials. It involves the enlisting of a fellow scholar to read, analyze, and critique your work. If my proposal passes review, then I will hopefully go under contract. My finished book manuscript will also have to go through review before it is published. While I wait for the review of my proposal, I have been working on completing the various sections on my manuscript that still need revising. If my proposal does not pass review at the press I am currently working with, then I will have to find another press and editor.

All in all, there are many steps that still need to be completed before my book is published. This process will continue to take a long time. But, I am not going to give up. Not yet. As I told a colleague recently, I have already put too much time and energy into this baby to let it go now. My research and my work are too important to put aside because the journey to completion is taking longer than most people would like. What’s more, my work seems even more relevant now given the recent progress of the amendment. I don’t give up…at least not easily. I guess, in the end, that is the lesson I want my daughter to take from this entire endeavor.

~Rebecca DeWolf, PhD

[1]Senator Charles curtis (R-KS) and Representative Daniel Read Anothony Jr. (R-KS) introduced the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) into Congress in 1923. Alice Paul of the National Woman’s Party (NWP) and her allies developed the amendment in an effort to ensure complete constitutional equality between men and women citizens. What I identify as the first ERA conflict lasted from the early 1920s through the early 1960s, as the amendment underwent an ardous journey through Congress. In the mid-1960s, it appeared as though amendment opponents had sucessfully quelled the ERA movement by promoting alternative comprehensive measures for enhancing women’s status. A combination of social developments and a re-energized female activism produced a reawakening of the ERA campaign effort that led to the ratification struggle of the 1970s, or whatI identify as the second ERA conflict. Congress passed the ERA in 1972. But, when the amendment reached its deadline on June 30, 1982, it remained three states short of the necessary three-fourths necessary for ratification of a constittuonal aendment. Thus, to this day, the amendment remains unratified.

[2]Mary Frances Berry, Why ERA Failed: Politics, Women’s Rights, and the Amending Process of the Constitution(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986); Jane Mansbridge, Why We Lost ERA(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1986). See also Janet Boles, The Politics of the Equal Rights Amendment: Conflict and Decision Process(New York: Longman, Inc., 1979); Gilbert Steiner, Constitutional Inequality: The Political Fortunes of the Equal Rights Amendment(Brookings Institution Press, 1985); and Joan Hoff-Wilson ed., Rights of Passage: the Past and Future of the ERA(Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1986).

[3]Rebecca DeWolf, “The Equal Rights Amendment and the Rise of Emancipationism, 1932-1946,” Frontiers 38, no.2 (2017): 47-80.

[4]William O’Neill, Everyone Was Brave: A History of Feminism in America(Chicago: Quadrangle Books, 1969); J. Stanley Lemons, The Woman Citizen: Social Feminism in the 1920s(Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1981); Susan Becker, The Origins of the Equal Rights Amendment: American Feminism Between the Wars(Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1981); Felice D. Gordon, After Wining: The Legacy of the New Jersey Suffragists, 1920-1947(New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1986); Christine Lunardini, From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman’s Party, 1910-1928(New York: New York University Press, 1986).

[5]Rebecca DeWolf, “Amending Nature: The Equal Rights Amendment and Gendered Citizenship in America, 1920-1963,” (PhD diss., American University, Washington D.C., 2014).