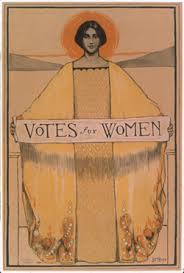

Over the course of the nineteenth century, the suffrage movement grew from a small, fractious campaign into a powerful, unified movement. As my last post discusses, the suffrage movement flourished partly because suffragists increasingly appealed to traditional images of womanliness as well as the racial prejudices of the white middle class. By the early twentieth century, the movement had further expanded to become not only an influential part in women’s organized activities, but also a prominent force in the spectrum of American politics. As a result, the passage of a federal amendment that affirmed women’s right to vote seemed increasingly possible.[1] There are three main reasons for why suffrage-ism became such an overwhelming force: the rise of the progressive movement; the evolution of suffragists’ tactics; and the decline of the masculine political culture of the nineteenth century.

The progressive movement, which roughly began around the early twentieth century, proved to be a tremendous boost for the suffrage campaign. For many progressives, woman suffrage was an essential means for purifying the public domain and securing their reform efforts. These efforts included pure food and drug legislation, protection for workers, an end to child labor, and legislation to curb political corruption. Progressive-minded women eventually turned to the suffrage movement in the early 1900s, because they often struggled to secure their reform agenda through the traditional routes of indirect influence. Leading progressive reformer, Jane Addams, for example, strongly supported federal woman suffrage. On woman suffrage, Addams argued in Ladies Home Journal that “one cannot imagine that they [women] would shirk simply because the action ran counter to old traditions.” [2] Overall, the progressive movement encouraged many civically active women to look to the ballot as a means for advancing their reform initiatives. [3]

The progressive movement, which roughly began around the early twentieth century, proved to be a tremendous boost for the suffrage campaign. For many progressives, woman suffrage was an essential means for purifying the public domain and securing their reform efforts. These efforts included pure food and drug legislation, protection for workers, an end to child labor, and legislation to curb political corruption. Progressive-minded women eventually turned to the suffrage movement in the early 1900s, because they often struggled to secure their reform agenda through the traditional routes of indirect influence. Leading progressive reformer, Jane Addams, for example, strongly supported federal woman suffrage. On woman suffrage, Addams argued in Ladies Home Journal that “one cannot imagine that they [women] would shirk simply because the action ran counter to old traditions.” [2] Overall, the progressive movement encouraged many civically active women to look to the ballot as a means for advancing their reform initiatives. [3]

The bold campaign of suffragist Alice Paul, and her National Woman’s Party (NWP), also mobilized support for the suffrage movement. Paul was a brilliant strategist when it came to attracting the attention of the press to the movement. For this reason, Paul was able to force the cause of woman suffrage to the forefront of public debate.[4] To illustrate, Paul organized a massive, dramatic suffrage parade during President Wilson’s inaugural celebration; the parade successfully captured the nation’s attention, because it featured more than eight thousand suffragists.[5] The NWP also picketed the White House, making it the first group to do so for a political cause. In the process, the NWP’s demonstrators were arrested and imprisoned on charges of obstructing traffic. After the NWP’s members protested their imprisonment with hunger strikes, they were forcibly fed, which NWP member Doris Stevens’ recorded in detail, in her 1920 account, Jailed For Freedom.[6] Above all, the NWP’s actions called national attention to what they understood to be the hypocrisy of a nation that championed democracy in World War I, while still denying its own female citizens the right to vote.

The tactics of acclaimed suffragist, Carrie Chapman Catt also contributed to the success of the movement, as she was able to harness the National American Woman Suffrage Association’s (NAWSA) powerbase and political influence. Catt’s “winning plan” helped to advance a federal suffrage amendment because it called for suffragists in states where women already had the vote to exert pressure on their national representatives. In addition, Catt, and her NAWSA colleagues, Maud Wood Park and Helen Gardener worked hard to convince President Wilson to support federal woman suffrage. They also conducted a massive lobbying effort to secure congressional support. Finally, Catt put her own pacifism on hold after the United States entered World War I in order to enhance the patriotic image of NAWSA and its campaign for woman suffrage.[7] While Paul and the NWP drew public attention to the cause of woman suffrage through militant action and civil disobedience, Catt and NAWSA mastered what historian Robert Booth Fowler has identified as “practical politics.”[8]

Lastly, the decline of the nineteenth-century masculine political culture also gave way to the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment (the constitutional act that affirmed women’s right to vote). In terms of background information, the rise of male suffrage in the nineteenth century produced a distinct political culture based on male bonding and partisanship. During this period, moreover, the dominant cultural consensus pushed men to focus on political parties and electoral politics while it instructed women to develop a politics of domesticity that centered on indirect influence through voluntary associations. By the early twentieth century, however, the ballot had become less important, because a shift in governance structure replaced the sources of political power away from mass politics and towards interest based groups.[9]

Historian Paula Baker even goes so far as to argue that when the ballot became less important, political participation declined as a crucial component to the formation of men’s gender identity. Because of this development, Baker concludes, “Men granted women the vote when the importance of the male culture of politics and the meaning of the vote changed. Electoral politics was no longer a male right or a ritual that dealt with questions only men understood.” In short, Baker’s argument suggests that women secured the right to vote at a time when the value of the ballot was on the decline.[10]

It is undeniable that Baker’s analysis provides important insights on the changes that reverberated throughout American politics during the early twentieth century. Still, we should not ignore the deep historical significance of the Nineteenth Amendment. To start, the amendment marked a profound rupture in America’s legal tradition. As scholar Reva Siegel puts it, by passing the Nineteenth Amendment, American legislators “were breaking with understandings of the family that had organized public and private law and defined the position of the sexes since the founding of the republic.”[11]

To be sure, since the Nineteenth Amendment only affirmed women’s right to vote, it ultimately failed to fully overturn the thrust of legalized sex discrimination. Additionally, as discussed in the first installment of this post, appeals made by many later suffragists to the mainstream cultural ethos of female virtue and social motherliness ultimately reinforced the concept of immutable sex differences, which further restricted women’s range of opportunities. And, what’s more, the racially charged atmosphere that plagued the suffrage movement especially in its later years not only created a hostile environment for black female activists, but also a deep sense of hypocrisy that severely limited the movement’s calls for equality.

To be sure, since the Nineteenth Amendment only affirmed women’s right to vote, it ultimately failed to fully overturn the thrust of legalized sex discrimination. Additionally, as discussed in the first installment of this post, appeals made by many later suffragists to the mainstream cultural ethos of female virtue and social motherliness ultimately reinforced the concept of immutable sex differences, which further restricted women’s range of opportunities. And, what’s more, the racially charged atmosphere that plagued the suffrage movement especially in its later years not only created a hostile environment for black female activists, but also a deep sense of hypocrisy that severely limited the movement’s calls for equality.

Now, you may think I am nuts, but I am still in awe of the suffrage movement. Yes, it had deep, deep flaws. And, yes, it could have, and it should have, gone further. And, we are right to judge its significant shortcomings. But, when you think of what it was able to achieve in the face of so many obstacles, it is quite an impressive thing to behold. To put it simply, when suffragists finally convinced American legislators to affirm women’s right to vote through the Nineteenth Amendment, they were dislocating the customary meaning of American citizenship from its traditionally masculine gender.

Now, you may think I am nuts, but I am still in awe of the suffrage movement. Yes, it had deep, deep flaws. And, yes, it could have, and it should have, gone further. And, we are right to judge its significant shortcomings. But, when you think of what it was able to achieve in the face of so many obstacles, it is quite an impressive thing to behold. To put it simply, when suffragists finally convinced American legislators to affirm women’s right to vote through the Nineteenth Amendment, they were dislocating the customary meaning of American citizenship from its traditionally masculine gender.

There is still significant work to be done before we can be assured that men and women are able to fully participate as citizens on the same terms. Looking forward, lets try to build a movement for equality that not only surpasses the traditional political divides of Republicans versus Democrats, but also avoids the destructive pitfalls of racial prejudices and gender stereotypes, which only serve to limit a person’s range of choice and individuality. Let’s recognize that we can only be assured of the law’s legal fairness when we know that the law will treat everyone fairly. After all, the concept of fairness entails that everyone enjoys its benefits. A society is not just, if its advantages only apply to some and not all.

In the end, the suffrage movement teaches us that the impossible can happen. Due to an undying determination and persistence that lasted for decades, women were able to secure the vote in a country that was founded on a profound commitment to the maleness of rights-bearing citizenship. Even so, we should learn from the movement’s flaws and strive to build a new campaign that pushes the concept of equality to its fullest extent.

In the end, the suffrage movement teaches us that the impossible can happen. Due to an undying determination and persistence that lasted for decades, women were able to secure the vote in a country that was founded on a profound commitment to the maleness of rights-bearing citizenship. Even so, we should learn from the movement’s flaws and strive to build a new campaign that pushes the concept of equality to its fullest extent.

As always, I would love to hear your thoughts and comments. Please sound off in the comments below.

~Rebecca DeWolf, PhD

[1]. Suffrage-ism became an overwhelming force by 1900. For contemporary accounts, see Carrie Chapman Catt and Nettie Rogers Shuler, Woman Suffrage and Politics: The Inner Story of the Suffrage Movement (New York: C. Scribner, 1923); Abigail Scott Duniway, Path Breaking: An Autobiographical History of the Equal Suffrage Movement in Pacific Coast States (Portland, OR: James, Kerns & Abbott CO., 1914); Inez Haynes Irwin, Up Hill With Banners Flying: The Story of the Woman’s Party (New York: Harcourt Brace, 1921).

[2]. Jane Addams, “Why Women Should Vote,” Ladies Home Journal 27 (January 1910): 21-22..

[3]. See Anne Firor Scott, The Southern Lady: From Pedestal to Politics (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1970); S. Sara Moonson, “The Lady and Tiger: Women’s Electoral Participation in New York City before Suffrage,” Journal of Women’s History 2 (Fall 1900): 100-135; Robyn Muncy, Creating a Female Dominion in American Reform 1890-1935 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991); and William H. Chafe, “Women’s History and Political History: Some Thoughts on Progressivism and the New Deal,” in Visible Women: New Essays in American Activism, eds. Nancy Hewitt and Suzanne Lebsock (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993), 110-118.

[4]. Linda Ford, Iron Jawed Angels: The Suffrage Militancy of the National Woman’s Party, 1912-1920 (Lanham, Md: University Press, of America, Inc., 1991).

[5]. Marjorie Spruill Wheeler, ed., One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement (Troutdale, OR: NewSage Press, 1995), 16-17.

[6]. Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright Publishers, 1920).

[7]. See Jacqueline Van Voris, Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life (New York: Feminist Press at The City University of New York, 1986); and Sara Hunter Graham, Woman Suffrage and the New Democracy (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1996).

[8]. Robert Booth Fowler, Carrie Catt: Feminist Politician (Boston: Northeaster University Press, 1986), especially chapter nine.

[9]. Scholars argue that the decline in voting turnout was due to changes in the party system and legal restrictions on voting. In particular, they contend that the decline in voting and partisanship created a space for the gradual rise of interest –based group politics and a bureaucratic regulatory state. See Walter Dean Burnham, “Theory and Voting Research,” American Political Science Review 68 (September 1974): 1002-1023; J. Morgan Krousser, The Shaping of Southern Politics: Suffrage Restriction and the Establishment of the One-Party South, 1880-1910 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1974); Richard L. McCormick, The Party Period and Public Policy: American Politics from the Age of Jackson to the Progressive Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986); and Michael McGerr, The Decline of Popular Politics: The American North, 1865-1928 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1986).

[10]. Paula C. Baker, “The Domestication of Politics: Women and American Political Society, 1780-1920,” American Historical Review 89 (June 1984): 645.

[11] Reva Siegel, “She the People: The Nineteenth Amendment, Sex, Equality, Federalism, and the Family,” Harvard Law Review 115, no. 4 (February 2002): 951.