The short answer is no. There are plenty of historians of women’s history who do not go into a detailed inspection of gender and there are plenty of gender historians who do not focus on women’s historical experiences in particular. To be sure, there are important connections between the two fields. Gender history developed in part from the field of women’s history and there are many historians, including me, who combine both fields in their research and writing. As well, both women’s history and gender history have helped to address the inadequacies of previously accepted male-centric histories, which had structured historical topics around the supposed achievements of great white men. Still, there are important differences between women’s history and gender history. While historians of women’s history foreground women as historical actors, historians of gender history focus on how ideas about what it means to be a man and a woman have shaped major historical struggles and events. Since we recently celebrated women’s history month, now is a good time to dissect the relationship between women’s history and gender history. As I suggest in my conclusion, both fields can help historians shed light on an emerging debate about civic rights that is taking form in certain social activist circles.

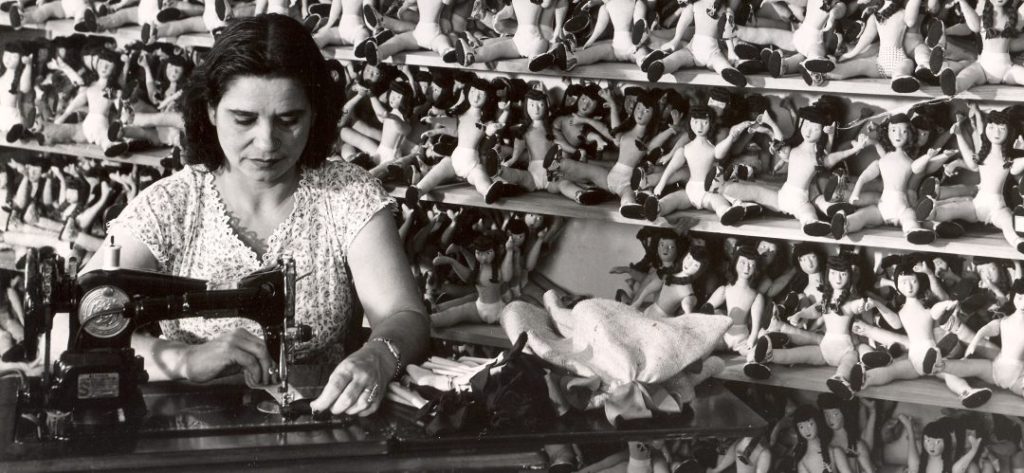

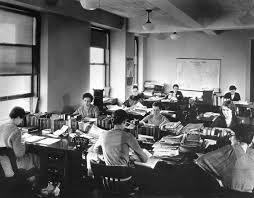

The earliest works on women in U.S. history date back to the nineteenth century. These works primarily focused on the overlooked contributions made by women to the creation of the United States and its history. Usually biographies of famous women, like the First Ladies, these studies primarily defined women by their relationship to famous men.[1]By the mid-1900s, historians interested in women’s history began to emphasize how women were historical participants irrespective of the men around them. For instance, historian Mary Beard in Woman as a Force in History (1946) demonstrated that women were always active players in society and not marginal or unimportant to U.S. history.[2] The early works in U.S. women’s history predominantly highlighted how women contributed to established historical narratives. By focusing on adding women into the conventional narratives, the initial works in women’s history failed to question or redefine major historical concepts and themes.

U.S. women’s history took greater shape as a distinct field in the late 1960s and 1970s as an outgrowth of the re-energized women’s activism of that period. Attention to women’s history surged as the civil rights movement and other social movements had inspired more women to explore the historical origins of sex discrimination. In the midst of this upwelling in women’s history, women’s historians sharply demonstrated that because previous historical accounts had largely ignored women’s experiences, historical narratives had produced misguided and inadequate depictions of U.S. history. By exploring primary source materials that historians had beforehand dismissed as inconsequential, and by engaging in critical re-analyses of traditional primary sources, historians of women’s history began to expand and even reconstruct previously accepted histories of industrialization, electoral politics, social reform movements, the foundations of the modern welfare state, as well as many other important topics. The pioneers of this “New Women’s History” included Gerda Lerner, Joan Kelly, Linda Kerber, Nancy Cott, Alice Kessler-Harris, and Linda Gordon.[3] As women’s history grew, historians in the field argued that their scholarship should not merely add a new set of women characters to the through lines of U.S. history but rather that their field should redefine and challenge the entire story of the United States.

A prominent theme in the scholarship of the 1970s rise in women’s history centered on the separate spheres paradigm of the mid-nineteenth century. Much of this research focused on the ways in which society directed women’s lives towards the family and the private domain of the home while it pushed men towards the wide world of politics, industrial work, and public life. In The Bonds of Womanhood (1977), Nancy Cott examined domesticity and sisterhood to emphasize the empowerment and autonomy women could sometimes enjoy in the domestic separate sphere. Cott maintained that the cult of domesticity was a force that led to an increased awareness of women’s potential influence, which planted the seeds for the formation of a prevalent feminist consciousness in the early twentieth century.[4]Likewise, historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg in her 1975 article, “The Female World of Love and Ritual,” explored the “homosocial” relationships of women in the nineteenth century that grew from women’s separate sphere. She contended that in some ways the separate spheres ideology actually empowered women because it helped women to forge powerful, deeply felt ties with one another.[5] These early works from Cott and Smith-Rosenberg demonstrate the balancing act historians of women’s history have tried to create between underscoring women ‘s victimization and oppression on the one hand and women’s agency and historical influence on the other. The struggle to find this balance continues to shape the field to this day.

By the early1980s, scholars started to pay more attention to the limitations of the separate spheres paradigm. Several historians pointed out that the separate spheres concept had little relevance to the lives of Black, working-class, or immigrant women. The separate spheres model also relied on primary source materials from New England, which had less significance for the lived experiences and historical trends that took form in the more southern and western regions of the United States. A number of scholars argued that middle-class women had more in common with men of their own social and economic class than with women from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Scholars also came to contend that the boundaries between public and private domains were actually more fluid than what had been portrayed by the writers of nineteenth-century prescriptive literature.

Because of the increasing emphasis on the diversity of women’s experiences—not their commonality—it was no longer sufficient to simply use the blanket term “women” when discussing topics in U.S. women’s history. Scholars now needed to be clearer about the range of social forces (such as race, class, ethnicity, religion, geography, age, and sexual orientation) that impacted the women that they were examining in their works. In other words, historians needed to be specific about exactly what group of women they were talking about. As well, historians came to increasingly highlight the conflicts among women and the unequal power dynamics influencing relations among women. Scholars who led the way in laying more emphasis on the diversity of women’s experiences as an organizing concept for women’s history include Deborah Gray White, Jacqueline Jones, Paula Giddings, Theda Perdue, Vicki Ruiz, and Lillian Faderman.[6]

Another trend that emerged in the 1980s, and that has proved to be tremendously influential in my own work, is the growing awareness of gender as a formative historical force. Gender broadly concerns the values and qualities a society attaches to men and women while sex refers to the general anatomical attributes found within the spectrums of male, female, and non-binary persons. Driven by the scholarly turn to poststructuralism, literary analysis, cultural anthology, and new cultural history, many historians moved away from the 1960s and 1970s emphasis on social and economic behavior to analyze the meanings and symbolic representation wrapped in the social and historical construction of gendered ideas. Michel Foucault’s immensely important theories on how the development of certain discourses have affected the creation of people’s identities has appealed to scholars who have sought to unravel the construction of gendered categories. These scholars argue that gendered notions such as masculine and feminine, womanly and manly, manhood and womanhood, are not essentialist, fixed, biological concepts. On the contrary, the meanings of gendered ideas are dependent upon their location in a given space and time. Since gendered ideas are socially and historically constructed concepts that have changed over time, they have inherent power dynamics embedded within them.

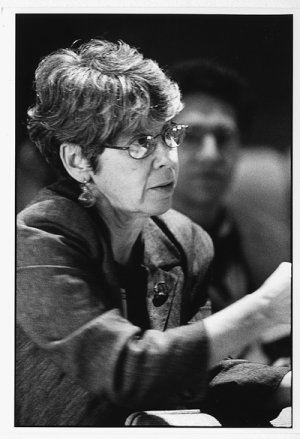

Joan Scott’s groundbreaking 1986 essay, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” brilliantly captured the growing literature that was illuminating the ways in which gendered discourses have molded power relationships and power struggles throughout history.[7] As an aside, and please forgive my bragging here, I met Scott several years ago after she had given a lecture on the resurgence of feminism in the 1970s. That talk, and my subsequent conversation with her, was one of my most eye-opening experiences I have ever had in my life. She has an awe-inspiring, brilliant mind. Okay, moving on…

Scott’s subsequent work, Gender and the Politics of History (1988), further developed the field of gender history by showing how gendered discourses can be deconstructed to reveal the power dynamics entrenched in the formation of political identities, social institutions, and social relations. In her work, Scott argued that the study of gender must go beyond the study of women. For Scott, gender history should not be the mere recounting of great deeds by great women. A proper gender analysis, she argued, should unearth how unequal relationships of power are developed around gender-infused ideologies and concepts. In Scott’s view, gender is a social construction in which women have been largely defined in relation to men, and in male-dominated terms. Society then presents those terms as objective observations. As a result, male dominance is erroneously rendered to be natural and inevitable. Overall, for Scott, taking apart the normative discourse surrounding gender standards, ideals, and boundaries will help scholars call greater attention to the political implications entrenched in gender and the often-discounted implicit operations of power that have shaped U.S society.[8]

As more scholars turned to gender as an innovative area of historical research in the late 1980s and 1990s, many women’s historians had already begun to wonder if studying women in isolation from men ran the risk of over isolating women’s history, by making it a small segment of the larger discipline, instead of fully integrating women’s experiences into the larger historical narrative. As these scholars acknowledged, women’s history is intimately related to men’s history, and neither can be fully understood without reference to the other. For many of these historians, the emergence of gender history presented the methodological solution for how to achieve an integrated historical analysis of men and women. [9]

Over the years, scholars of gender history have produced seminal works that have redefined core aspects of U.S. history. In Gender and Jim Crow (1996), for instance, Glenda Gilmore explored the interconnected roles played by racialized and gendered constructs in North Carolina politics to reveal the significant role of Black women in the political history of the Jim Crow era.[10] Kristin Hoganson’s Fighting for American Manhood (1999) provided a new understanding of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American wars by highlighting how gendered ideas about citizenship influenced the rise and fall of the U.S.’s imperialist impulse.[11] Another work that helped to reformulate a major section of American history is Kathleen Brown’s Foul Bodies (2009). In this work, Brown examined the gendered idea of “body work” to capture the array of “cleaning, healing, and caring labors” that women carried out in early America to show how such labor structured the entire social and political system.[12] As well, Kyle Cuordileone’s Manhood and American Political Culture in the Cold War (2005) offered a new account of the political culture of the 1940s and 1950s that emphasized how gender anxieties about men and women’s proper roles shaped the politics of the Cold War.[13] These are just a few of my favorite works in the field of gender history. By destabilizing the concept of gender to show its historical and social underpinnings, the field of gender history now contains many studies that have helped to rewrite major components of U.S. history.

When I was a graduate student completing my MA, and then later my PhD, I encountered several discussions among scholars about the possibility that gender history might replace women’s history.[14] Now that the academic world has recognized gender as a useful tool of historical analysis, was there a need for a separate academic field dedicated to women’s historical contributions? Because history textbooks and mainstream historical narratives continue to rely on the great white man theory of history (a tendency to frame historical events around famous white men), it has become clear that women’s history remains quite valuable and necessary in order to push society towards the understanding that women are historical forces in their own rights. Thus, there are still plenty of influential historians that continue to center their analyses on women’s historical experiences.

Nowadays, several historians do a combination of both women’s history and gender history by not only foregrounding women as historical actors but also combing source materials for clues about how men and women have both been shaped by gendered beliefs, practices, and institutions. In my forthcoming book, Gendered Citizenship, for instance, I explore the competing civic ideologies rooted in the original conflict over the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) to unearth the gendered ideas that have shaped our conceptions of rights and citizenship. While my work looks at an array of women involved in the original ERA conflict, I also call more attention to the range of men who participated in the struggle. To be sure, women are at the center of my historical analysis, but the heart of my story revolves around the gendered ideas wrapped in the changing nature of America citizenship.

As scholars have given more attention to exploring the production and deployment of gendered categories, many scholars have also sought to unfix the concept of binary sex differences. For example, Thomas Laqueur’s Making Sex (1992) illuminated the history behind Western societies’ scientific conceptions of sexual difference. In his work, Laqueur retraced the dramatic changes in Western views of human anatomy from the previously dominant one-sex model (where the female body was seen as essentially an imperfect version of the male body) to the now prevalent two-sex model (where men and women are understood to be two contrastingly different types of bodies).[15] Studies like Laqueur’s work, seek to understand how the concept of biological sex is also a product of society and history. For them, shifting ideas about biological maleness and femaleness are not passive backdrops to the ever-changing concept of gender. This field of study developed from anthropological research on cultures where notions of the human body are not limited to a female-male binary. These studies are also indebted to the incredible influence of theorist Judith Butler and other scholars in fields of performativity and queer studies.[16]

One of the most significant books to interrogate the concept of a male/female sex binary is Joanne Meyerowitz’s How Sex Changed (2002). In her work, Meyerowitz looked at the life of transgender woman Christine Jorgensen in the mid-to-late twentieth century to argue that there is nothing inevitable, natural, or inescapable about our society’s understanding of sex, sexuality, and gender. Meyerowitz showed that men and women have not always been seen as direct opposites, and that the categories of sex, gender, and sexuality are historical products that are constantly being renegotiated. In all, works like Meyerowitz’s study have destabilized the concept of the biological two-sex model to shed light on how human anatomy also exists on a series of spectrums, which has not been fully captured by the simple male vs. female binary model. [17]

In recent years, I have seen an uptake of an essentialist way of thinking about gender and sex among certain women’s rights advocates. These activists have maintained that while gender can be fluid and flexible, sex is a stable category that has not changed over time. Because they believe biological femaleness is a constant and fixed concept, they maintain that women are entitled to certain sex-specific rights that should not be applicable to men, trans-persons, and nonbinary individuals.[18] However, as I have found in my own research on the history of American citizenship, when groups commit themselves to a hierarchy of rights and to essentialist forms of thought, they run the risk of discounting people’s qualities from the start, which prohibits people from functioning as individuals. When you argue that rights should be dependent on one’s sex, you are implying that rights can also be restricted because of one’s sex. That seems to be a far cry from the hope for equality and equity embedded in women’s history and gender history, or from what Joan Scott has described as the “relentless interrogation of the taken-for-granted.”[19]

[1] See, for example, Alice Morse Earle, Colonial Dames and Good Wives (New York: Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1895).

[2] Mary Beard, Woman as a Force in History (New York: Macmillan, 1946).

[3] Gerda Lerner, “U.S. Women’s History: Past, Present, and Future,” Journal of Women’s History 16, no. 4 (2004): 11-12; Joan Kelly, Women, History, and Theory (The University of Chicago Press, 1986); Linda Kerber, Women of the Republic: Intellect and Ideology in Revolutionary America (Williamsburg, VA: Institute of Early America, 1980); Nancy Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood: “Woman’s Sphere” in New England, 1780-1835 (Yale University Press, 1977); Alice Kessler-Harris, Out to Work: A History of Wage-Earning Women in the United States (Oxford University Press,1982); Linda Gordon, Woman’s Body, Woman’s Right: the History of Birth Control Politics in America (Viking/Penguin, 1976).

[4] Cott, The Bonds of Womanhood.

[5] Carroll Smith-Rosenburg, “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Women in the Nineteenth Century,” Signs 1, no. 1 (Autumn 1975): 1-29.

[6] Deborah Gray White, Ar’nt I am Woman: Female Slaves in the Plantation South (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1985); Jacqueline Jones, A Labor of Love, a Labor of Sorrow: Black Women, Work, and the Family from Slavery to the Present (Basic Books, 1985); Paula Giddings, When and Where I Enter: The Impact of Black Women on Race and Sex in America (Bantam Books, 1988); Theda Perdue, Sifters: Native American Women’s Lives (Oxford University Press, 2001); Vicki Ruiz, Cannery Women, Cannery Lives: Mexican Women, Unionization, and the California Food Processing Industry, 1930-1950 (University of New Mexico Press, 1987); Lillian Faderman, Odd Girls and Twilight Lovers: A History of Lesbian Life in Twentieth-Century America (Columbia University Press, 1991).

[7] Joan Scott, “Gender: A Useful Category of Historical Analysis,” American Historical Review 91, no. 5 (December 1986): 1053-1075.

[8] Joan Scott, Gender and the Politics of History (New York: Columbia University Press, 1988).

[9] See, for example, Natalie Zemon Davis, “Women’s History in Transition: The European Case,” Feminist Studies 3 (1976): 83-103.

[10] Glenda Gilmore, Gender and Jim Crow: Women and the Politics of White Supremacy in North Carolina, 1896-1920 (University of North Carolina Press, 1996).

[11] Kristin Hoganson, Fighting for American Manhood: How Gender Politics Provoked the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars (1999).

[12] Kathleen Brown, Foul Bodies: Cleanliness in Early America (Yale University Press, 2009), 5, 4, 11, 361-63.

[13]. Kyle Cuordileone, Manhood and American Political Culture in the Cold War (New York: Routledge, 2005).

[14] See, for example, Alice Kessler-Harris, “Do We Still Need Women’s History,” Chronicle of Higher Education 54 (7 December 2007), B6-B7.

[15] Thomas Laqueur, Making Sex: Body and Gender from the Greeks to Freud (Harvard University Press, 1992).

[16] See Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (Routledge, 1990); Judith Butler, Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex” (Routledge, 1993); Will Roscoe, Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America (St. Martin’s Press, 1998); and Cornelia H. Dayton and Lisa Levenstein, “The Big Tent of U.S. Women’s and Gender History: A State of the Field,” The Journal of American History 99, no. 3 (December 2012): 793-817.

[17] Joanne Meyerowitz, How Sex Changed: A History of Transsexuality in the United States (Harvard University Press, 2002).

[18] In particular, I am thinking of activist groups, sometimes called “trans-exclusionary feminists,” who have taken issue with the rights of transgender men and women, and non-binary individuals.

[19] See Joan Scott, “Feminism’s History,” Journal of Women’s History 16 (summer 2004): 10-29, especially page 23.