A month before the madness of COVID-19 descended upon us, I watched Marielle Heller’s brilliant film, “A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood,” starring Tom Hanks as Fred Rogers, the beloved children’s’ television host of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. The film unearths the long-forgotten virtues of patience, listening, kindness, and the embrace of one’s feelings. I found the film transformational. Yes, even then, when many of us, myself included, enjoyed a relative confidence in the world’s security. Now, it seems, COVID-19 has ripped our world apart in ways that we had once refused to entirely admit were possible. From then till now, I have spent a considerable amount of time reflecting on Fred Rogers’ life and his teachings. In view of the current turmoil confronting us all, I think it’s time to lean more fully into Mister Rogers’ message.

In 2003, Rogers passed away, relatively quickly, from stomach cancer. In 2018, my father also passed away from stomach cancer. As is usually the case with cancer, it was devastating for me and my family to watch my father’s illness take over his life. Over a year and a half ago, my gastroenterologist diagnosed me with an autoimmune disorder. That disorder has put me at a higher risk for developing stomach cancer and, as a result, I now face a lifetime of undergoing endoscopic procedures every 1-2 years to monitor the progress of my disease and check for malignant growths in my stomach. That link to stomach cancer aside, there is something else about Mister Rogers’ story that has captivated me and, I believe, it can also serve as a timely lesson for us all, which is the absolute beauty of his calls for empathy.

Fred Rogers was a “peculiar man,” according to Tom Junod, the once-cynical journalist who had penned the original story that inspired Heller’s film. In a recent article for The Atlantic, Junod explains that it was not Rogers’ “goodness but rather the peculiarity of his goodness that ha[d] made him, sixteen years after his death, triumphant as a symbol of human possibility…”[1] Fred McFeely Rogers was born in 1928 in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, which is close to Pittsburgh, to a decently wealthy family. Rogers, though, was a sickly child; when he was young, he had suffered from rheumatic fever and asthma. Because of his illnesses, his protective parents practiced social distancing by often keeping Rogers indoors and away from other children. His childhood, then, was frequently occupied by the depths of loneliness. But, as Jeanne Marie Laskas, a journalist and friend of Rogers, describes in the New York Times, it was during those periods of childhood solitude that Rogers first discovered his passions for storytelling, music, and self-reflection.[2]

In the early 1960s, Rogers graduated from Pittsburgh Theological Seminary and was ordained as a minister of the United Presbyterian Church. Instead of taking a position as a pastor of a church, Rogers’ decided to minster to children and their families through television. Rogers, however, joined the conduit of television as a reformer. Before starting his own program, he had found it disturbing that other adults were wasting the potential of television by sheepishly entertaining children with simple and demeaning hijinks, like pie throwing. Although Rogers consciously avoided conveying overtly religious convictions in his program, he did envision the space between the television set and the eyes of his audience as a sacred area that he treated it with the utmost respect.[3]

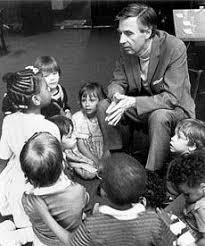

In a mission to make the medium of television less irreverent, Rogers taped almost 1,000 episodes of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood from 1966 to 2000. One of the main messages of his program was quite straightforward: speak to children as attentively and respectfully as you would speak to adults, and speak to adults with the knowledge that every adult was once a child too.[4] As Rogers later explained it to Jeanne Marie Laskas, he was trying to create “an atmosphere that allow[ed] people to be comfortable enough to be who they are.” He didn’t want, in his words, “to superimpose anything on anybody.” It was his belief that, if given a comfortable and understanding atmosphere, all children could blossom “in their own way.”[5]

Rogers’ was a lifelong collaborator, and follower, of Dr. Margaret McFarland, a child psychologist at the University of Pittsburgh. McFarland, along with her colleagues, Dr. Benjamin Spock and Dr. Erik Erikson, reshaped the study of childhood development through their research on children’s emotional landscape. McFarland, for example, inspired Rogers to explore the ways in which empathy for people’s childhood experiences could help us better accept ourselves and others. In Rogers’ mind, we all needed to recognize that even the most detestable adult was once a child too and that that person’s atrocious behavior was most likely due to invalidating and traumatizing experiences from their childhood.

It was McFarland, moreover, who instructed Rogers to adopt the saying: “Anything human is mentionable, and anything mentionable is manageable.”[6] As Rogers later explained that saying, it was understandable, in his mind, for adults and children to find certain things hard to talk about. But, he asked, “Don’t you often find that just having a good listener makes your upsetting times more manageable?” For Rogers, the sheer act of talking about daunting feelings to someone else could help reduce the overwhelming and, seemingly, uncontrollable aspects of those feelings. When we share our feelings, Rogers maintained, it reassures us that we are not alone and it gives us the confidence to realize that those scary feelings are natural and, most of all, acceptable. From Rogers’ perspective, the best way to stop, or prevent, a person from committing a hurtful act was to confront the principal feelings of insecurity that often push people to behave in hateful ways. Everyone, but most especially children, need to feel safe in the awareness that they have the potential to create fruitful connections with others.[7]

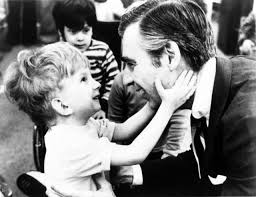

When we unpack it, though, Rogers’ underlying message was quite radical and that is what makes it so special. “It’s not the honors and the prizes and the fancy outsides of life which ultimately nourish our souls,” he once told his friend Jeanne Marie Laskas, “it’s the knowing that we can be trusted, that we never have to fear the truth, that the bedrock of our being is good stuff.”[8] Acceptance was at the heart of Rogers’ philosophy. Acceptance, love, and empathy. In Rogers’ view, people thrive when they have a sense of belonging; when they are certain that their feelings are important to others, when they know that they are lovable, and, in turn, when they know that they are capable of loving.[9] As he described it, “Since we were all children once, the roots for our empathy are already planted within us. We’ve known what it was like to feel small and powerless, helpless, and confused. When we can feel something of what our children might be feeling, it will help us begin to figure out what our children need from us.”[10]

Rogers believed that it was important for caregivers to engrain the seeds for their children’s emotional security. The essential element to children’s development, Rogers insisted, was the experience of their caregivers’ unconditional love, whoever those caregivers may be. In Rogers’ view, children need to feel confident in the knowledge that they can share their feelings with their loved ones and in the reassurance that they will not be abandoned or rejected by their grownups for showing disagreeable emotions.

This type of unbounded acceptance animated Rogers’ calls for radical kindness. He wanted everyone to remember that they were once children too. If we could all recall that eager search for recognition that fills childhood, then, he believed, we could discover more compassion and affinity for one another. But he was careful not to overly confuse acceptance with approval. He cautioned that it was perfectly understandable to disagree with others and dislike how someone acted. And, it was perfectly reasonable to want our loved ones to improve themselves. Yet, he made it clear that he appreciated that there was an “inside story to every outside behavior.”[11] While he might disapprove of someone’s actions, he was cautious not to make self-righteous, value judgements of others to make it clear that he would always be open to receiving a person’s thoughts and feelings. I believe, he once wrote, that “deep within us—no matter who we are—there lives a feeling of wanting to be lovable, of wanting to be the kind of person that others like to be with.”[12]

Rogers was not a saint, though. “Just don’t make Fred into a saint,” is the warning that we often hear from Joanne Rogers, Mister Rogers’ widow. “If you make him out to be a saint,” she further explained in one interview, “people might not know how hard he worked.”[13] Joanne Rogers, now 92, was married to Fred Rogers for more than 50 years. Throughout that time, she witnessed firsthand how hard Rogers worked on himself and his relationships. Of course, the extensive discipline and the control that he employed to balance his emotions and direct his energy is awe-inspiring. But, Joanne, and others who knew him, warn that if we make him into an otherworldly, inhuman being, we will fail to realize how we can all develop his level of focused empathy.[14]

A core principle that underpinned Rogers’ empathetic outlook on life was the notion that feelings needed to be permissible, but actions had to be limited. Rogers strongly believed that when we shame others for experiencing negative emotions, we not only fail to resolve crucial issues, but we also widen the communication gaps between ourselves and others. From his perspective, it was completely normal to feel angry, anxious, or sad. The pivotal element, though, was to find productive routes for guiding those feelings towards non-destructive habits and techniques. As he explained in one of his parenting guidebooks, “Destroying our own block buildings, pounding our own clay creations, scribbling over our own drawings—all these aggressive acts can vent anger in permissible ways.”[15]

Moreover, Rogers recommended that parents, and other caregivers of children, avoid dismissing their children’s negative feelings. He suggested that instead of denying, downplaying, or criticizing the possible reasons for a child’s frustration, a caregiver should give that child their full attention and listen to them. Through the simple act of listening to a child talk about their anger, Rogers maintained, caregivers can show just how deeply they valued that child’s feelings. He also advised against the all-too-frequent tendency of many parents to rush out and attempt to “fix” their child’s problem. Be a listener, not a problem-solver was a central motto for Rogers. Parents and caregivers can assist a distressed child by acknowledging the child’s feelings and helping him or her find a description for their feelings. To Rogers’ mind, it was crucial for caregivers to convey to their children that it was safe for them to fully experience the range of human emotions and to show children that there was a grownup to help them process even the most upsetting of feelings.

On one level, then, Rogers sought to help children learn how to feel secure in their emotional terrain. But, on a more profound level, Rogers realized that adults also needed guidance on how to expand their expressive intelligence. As Rogers explained it, “The anger we feel towards our children often comes from our own needs…Sometimes when our children are dependent and whining, we might feel our own impulses to be plaintive and demanding, too. We don’t like it. We don’t want to be reminded of those feelings in us, and so we might even surprise ourselves by reacting really strongly to our children’s whining.”[16] Parents often internalize and personalize their children’s bad behavior as a condemnation of their caregiving abilities and, ultimately, as a rejection of themselves. For example, when a child throws a fit at a store, time after time a parent will lose their patience and panic because they feel that other adults are judging them as a bad parent who lacks control over their children. I certainly have felt that way. And, I know that for myself, when I have tried to prepare an appealing meal for my children, and they refuse it outright even before tasting it, I not only feel hurt, but also incredibly frustrated that my own children won’t give my cooking skills a chance. But that’s the crucial component—unraveling the strands of our own emotional knots, can move us towards appreciating the reasons for children’s emotional eruptions. “When we begin to understand some of the many feelings we bring to our parenting,” Rogers concluded, “we can be more forgiving of ourselves.”[17]

When Rogers spoke with friends and loved ones, he often described his television program as “tending the soil” that would allow his viewers to forge their own emotional and spiritual nourishment.[18] That was the mission for his work. To be sure, he didn’t advocate for an unhinged explosion of emotional outbursts. But he did believe that we should allow for the expression of all feelings, especially negative ones, while also learning how to channel those feelings in healthy directions. Encouraging others to be comfortable with their honest, vulnerable selves, negative feelings and all, was the hallmark of Rogers’ belief system.[19]

Now, please be patient with me as I attempt to be philosophical in my concluding remarks. At the heart of Rogers’ worldview laid a binary interplay in which people either acted as acceptors or rejectors. Rogers was careful to outline the contours of that dynamic in many of his teachings. As I suggested above, he believed that a deep-seated fear over the prospect of rejection or abandonment caused people to act in hurtful ways to one another.

The anxiety that a person experiences over the possibility of rejection can often drive that person to act as a rejector themselves. The defensive thought process that underlies this preemptive move centers on the desire to hurt someone before you can be hurt yourself. If you sense that you are feeling or acting in a way that someone else could disparage, you might find yourself lashing out first in a partially subconscious effort to justify your original behavior and to avoid being the target of criticism. Even though so many of us are probably quite familiar with this thought process, it is still an unproductive way to live one’s life. As Rogers advised over and over again, negative behavior can only breed more negative behavior. Rejecting others or acting in a way that dismisses and shuns another person’s feelings, will only trigger more rejection by them and by you, which then spurs on the pattern of hurt and negativity.

The solution for breaking the negative cycle of neglect and disdain is to show more compassion, grace, and respect for the emotions that reverberate in all of us. We need to learn how to become acceptors of feelings, and not simply rejectors. We need to resist the conveniency that comes with judging, disavowing, and recoiling from other people when they show upsetting emotions. There is a commonality of human emotions that we all share. Each one of those emotions is real and each one of them is as a valid form of the human experience. The principal factor is how we deal with the distressing emotions that we feel and that we witness in others. Receiving feelings by allowing yourself, and others, to journey through those emotions in productive and permissible ways is essential for cultivating the emotional well-being that we all need to thrive. I know this is anything but an easy process, as it has been an absolute challenge for me to become more forgiving of myself and others. But I have grown to see that when we are open to the range of emotional backdrops that encapsulate the human experience, we are better able to create lasting connections between ourselves and others. Through those connections we can build the loving bonds that will allow us to better accept ourselves and to ultimately find peace in life.

[1] Tom Junod, “My Friend Mister Rogers,” Atlantic December 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2019/12/what-would-mister-rogers-do/600772/.

[2] Jeanne Marie Laskas, “The Mister Rogers No One Saw,” New York Times, 19 November 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/11/19/magazine/mr-rogers.html.

[3] Junod, “My Friend Mister Rogers.”

[4] Junod, “My Friend Mister Rogers.”

[5] Laskas, “The Mister Rogers No One Saw.”

[6] Laskas, “The Mister Rogers No One Saw.”; Fred Rogers, You are Special: Neighborly Words of Wisdom from Mister Rogers (Penguin Books, 1994), 97-98.

[7] Rogers, You are Special, 115-116.

[8] Laskas, “The Mister Rogers No One Saw.”

[9] Rogers, You are Special, 21.

[10] Fred Rogers, The Mister Rogers Parenting Resource Guide: Helping to Understand Your Young Child and Encourage Learning and Pretending (Philadelphia: Courage Books, 2005), 15.

[11] Rogers, You are Special, 39.

[12] Rogers, You are Special, 3.

[13] Amy Kaufman, “How Befriending Mister Rogers’ widow allowed me to learn the true meaning of his legacy,” Los Angeles Times, 26 November 2019, https://www.latimes.com/entertainment-arts/movies/story/2019-11-26/mister-rogers-widow-legacy-a-beautiful-day-in-the-neighborhood.

[14] Laskas, “The Mister Rogers No One Saw.”

[15] Rogers, You are Special, 71.

[16] Rogers, The Mister Rogers Parenting Resource Guide, 17.

[17] Rogers, The Mister Rogers Parenting Resource Guide, 17.

[18] Amy Hollingsworth, The Simple Faith of Mister Rogers: Spiritual Insights from the World’s Most Beloved Neighbor (Thomas Nelson, 2005), 38.

[19] Ibid., 68.